It took a little over three months for me to experience my first major occurrence of white supremacy in the US. It came one week after the Half Moon Bay shooting and the Monterey shooting (which was the 33rd American mass shooting in 2023, by the way)

I moved here in late October, shortly after hearing friends and family questioning me about the political climate in this country. That climate is cold. I’d call it permafrost. Frozen in time, and despite the warmth of many people in this crazy country, there’s hardly any movement, it seems.

Moving to America has cost me a lot, and it still does. It takes bravery to find a home here. Uncle Sam never fully lets you be free. While being here, it encapsulates you into dynamics you haven’t experienced before. Making you think this is needed to live a happy, rich life. All this anxiety, pain, dirt, and inaccessibility supposedly are worth it when it’s a life that’s worth living. A life that could mean something, even though it’s lived on the periphery of the margins along 300 million others. This is no life to be proud of. But it’s a life documented. And perhaps you could say it is exactly the lives on the fringes of society that seem to be deserving of documentation: Robert Frank and Dorothea Lange versus Slim Aarons and Richard Avedon.

In Los Angeles, where I live, there are cameras everywhere. This is where movies are made, where stars live, where possessions need to be protected, and where some deem it necessary to keep certain people away. Looking down and looking up are all done by the same device anyway: the camera.

The camera has always been a very powerful device. Who gets to decide what moment is captured? And what is being documented? As many before me have pointed out, it is no coincidence that photography is associated with violent terms such as “shooting” and “capturing.” To helm a camera means to have power over a subject. Power that is as dangerous as it is beautiful.

In essence, photography is setting the time still. That time freeze is in the hands of the cameraperson or photographer. And one fraction of a second can make a difference. It is a matter of taking a moment, grabbing it, and holding on to it forever. Video is a sequence of that. Multiple moments on a long string of film, putting thousands of photos in succession and creating the illusion of movement. It’s important to stress the illusionary element in this case. Because as I said earlier, in a country that presents itself as a land of the free, the medium of photography and film can hardly be seen as an encouraging movement. The videos seem to be moving, and yet, time is standing still.

In a way, the power of photography relies on the person who presses the shutter or record button. While one has the power to set time still, the other creates movement. It makes me wonder what happened when young photographer Tyre Nichols pressed the shutter button of his camera in Memphis. Did he stop the time when he made his favored landscape photos? If he aimed his shooter at his subject, did that make his subject freeze?

On Tyre Nichols's website, he highlights a quote by Joel Strasser saying: "A GOOD PHOTOGRAPHER MUST LOVE LIFE MORE THAN PHOTOGRAPHY ITSELF." The pitch-black irony of this quote doesn’t escape me. His About section reads:

“Photography helps me look at the world in a more creative way. It expresses me in ways I cannot write down for people. I take different types of photography, anywhere from action sports to rural photos, to bodies of water, and my favorite.. landscape photography. My vision is to bring my viewers deep into what I am seeing through my eye and out through my lens. People have a story to tell why not capture it instead of doing the "norm" and writing it down or speaking it.”

As someone who has had the privilege to work with many different photographers, I sometimes wish I had the power to express myself through photography or film. In some occasions, such as these, words can only hint at the essence. And continuing this exploration of the concept of time, I’m pretty sure that words, at least mine, will always come too late.

Tyre Nichols, a 29-year-old photographer, is dead. Killed weeks, days, hours, and minutes ago by five police officers who decided it was their time to abuse their power. Body cams and security cameras filmed the whole thing, recording Tyre calling for his mom while he was beaten to death a mere 60 yards away from his mother’s home.

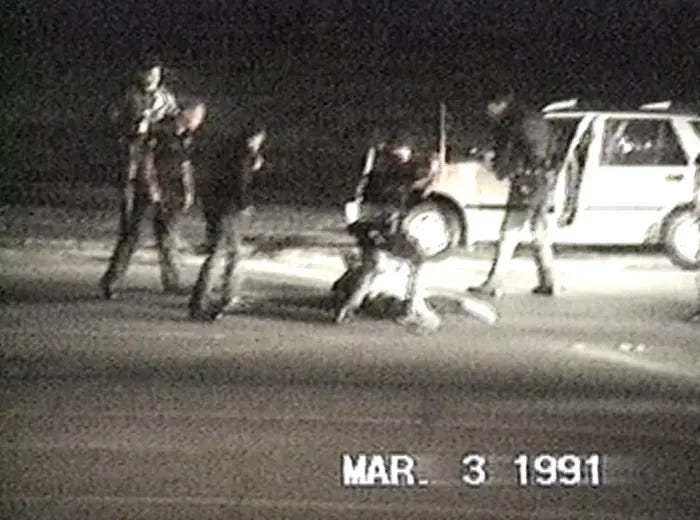

It took me a few weeks to process this. But as America does, America moves on. There are football games to be played. There are award snubs to be worried about. Those videos of Tyre’s beating, announced and released as if they were some new Netflix movie, did not move anything forward. You might say they put us back to March 3, 1991, but I don’t even think it really did that. See, for the rest of the world, America lives in a vacuum. It doesn’t move forward or backwards. It moves sideways. There is no past or future, only America. America first, America last, America everything in between.

In America, this winter, but also ever after, time does not move. When you realize that, you realize that it does not matter how much power the maker of a photo or video has. That video or photo will never be able to capture the harsh reality of everyday moments.

I’m going into my fourth month in America. Which ironically is Black History Month. It’s the shortest month of the year, but for a month of reliving national traumas, 28 days seems like a very long time. We’ll watch movies and photos of a bygone era. We’ll watch frozen moments of the winters behind us while this cold American winter continues. That winter is cold and stays cold. It is white. It is harsh. And it’s never been easier.