March 26, 2021, will always be the day I cried while running. I’ve probably clocked over 1,000 runs since, but none were as emotional–not even the milestones or races. It could’ve been the cold Amsterdam wind that morning or my contacts bugging in my crusty eyes. But the London Symphony Orchestra guiding my stride and Pharoah’s “budulupbudulp” (or something of that order) narrating my steps brought me emotionally over the bridge. Promises.

I have often been ridiculed for my music choices. As a student, I worked in retail, and my colleagues would pretend to walk through a jungle if they heard one of the songs on my playlist come up. Birds, shakers, Rhodes, harmoniums, those sounds are my home. It’s what I read, write, and think to. They align me with my surroundings and help me make sense of things.

Whatever neurodivergent label corresponds to that, I don’t know. I was tested for autism once, but they weren’t positive. But what I do know is that music, especially in portable carriers, is the ultimate way to acclimate. Earphones, whether wired or wireless, in-ear or over, cheap or expensive, are my portal to home. They’re a protective bubble in which I navigate the world. And when I was running that cold morning in 2021, that bubble was perfect.

Sam Shepherd, better known as Floating Points, composed a nine-piece suite for the London Symphony Orchestra. He invited Pharoah Sanders, 80 years young then, to join in. The result is an album that starts with a whisper and gradually becomes louder and louder until a euphoric cry is found in Movement 6. While the orchestra moves back and forth and slowly but surely washes over you like a wave on the shore, Sanders’ playing is pensive. He’s not just blowing his horn for the sake of playing. He listens.

Jazz musicians are improvisers. But whatever the word improviser might mean, they always know what they’re doing. The magic of Pharoah is that it seems like Pharoah is figuring it out as he plays. Sprinkling some airy notes on the arrangement to see how it turns out. In a way, Sanders feels like a companion. It’s as if he sits beside you conversing, listening to Shepherd’s composition, pointing out its strengths, surprises, and movements.

It wouldn’t be surprising if that’s how he went into the recording sessions. Not to play along but to add commentary. In one of his last big interviews, Sanders told New Yorker’s Nathaniel Friedman that he no longer listened to music. He only listened to sounds: “waves, trains, airplanes.”

In the same piece, Sanders said, “A lot of time I don’t know what I want to play. So I just start playing, and try to make it right, and make it join to some other kind of feeling in the music. Like, I play one note, maybe that one note might mean love. And then another note might mean something else. Keep on going like that until it develops into—maybe something beautiful.”

Sanders hasn’t always been playing like this, but he has been playing like this forever. Born in Little Rock, Arkansas, Farrell Sanders's career took him to Sun Ra’s Arkestra, John Coltrane’s band, and eventually his own. He found his own in “spiritual jazz,” creating beautiful songs like Astral Travelling, The Creator Has A Masterplan, Love Will Find A Way, and Black Unity—vehicles for intense noise but balanced with sensitive harmony. He was always leaving room for the listener to compile their own thoughts.

The best example of a record that does that is Pharoah, his eponymous album initially released in 1977 by India Navigation. The album features the beautiful 20-minute-long piece Harvest Time. Harvest Time was the soundtrack to my BA thesis. A low-res rip found by the YouTube algorithm, uploaded by an account named “spiritualarchive,” which gave me a filtered guitar, a funky bass, a compulsive harmonium, and Sanders’ hazy sax sounds to fuel me at the end of a strenuous academic journey. In bleak, grey study halls at the University of Amsterdam, my earphones painted me a colorful world, invited into by Pharoah Sanders, his wife Bedria, and Tisziji Muñoz’s hypnotic guitar play. Never too full. Never too grand. But grand enough to elevate me to higher levels. Both in thinking and in feeling.

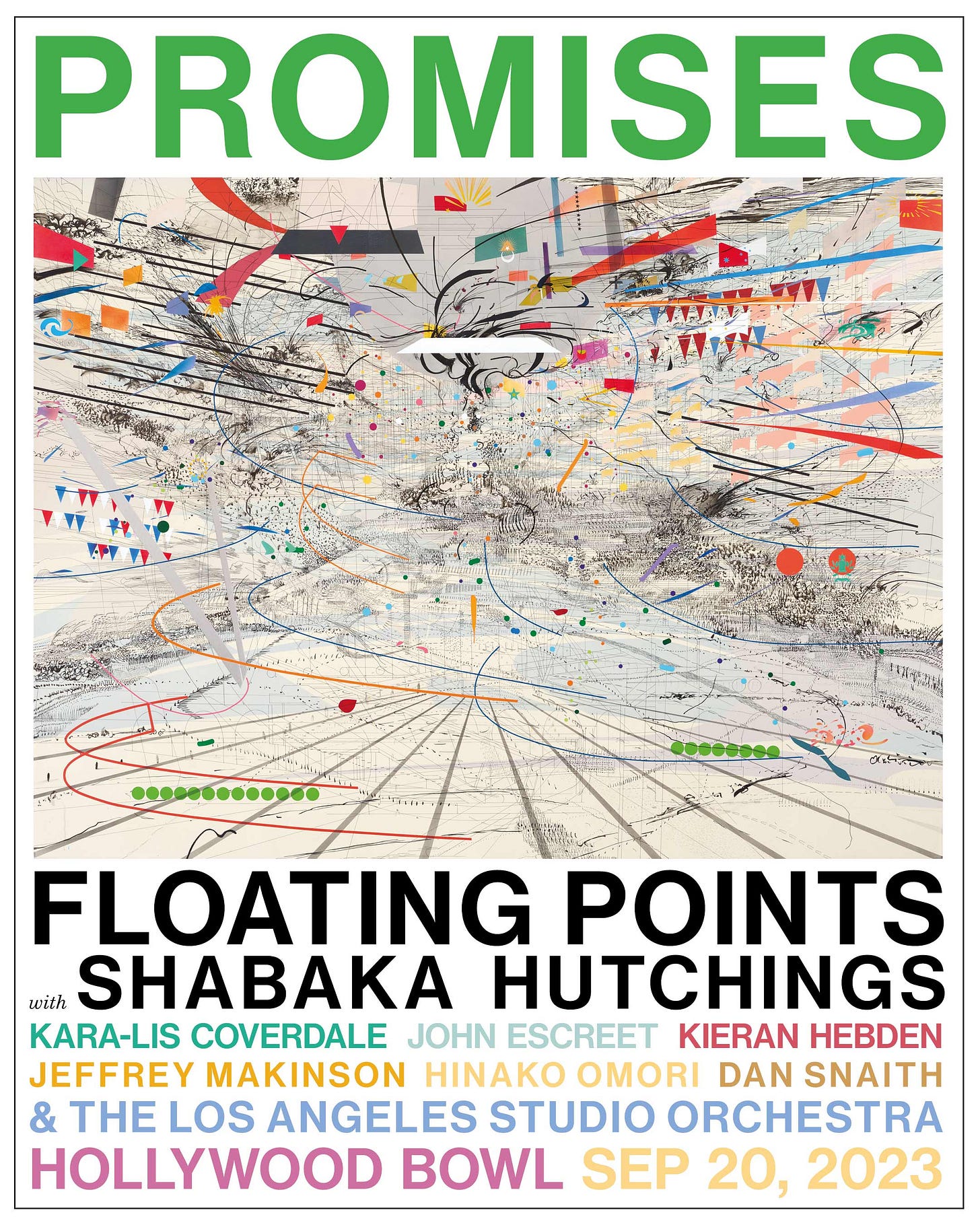

Of course, it’s not a coincidence that Luaka Bop, the label founded and co-owned by Talking Heads’ David Byrne, reissued Pharoah this week. This week is also the first and (for now) only time Promises (also on Luaka Bop) could be heard live. Yesterday, Sam Shepherd played alongside Kara-Lis Coverdale, John Escreet, Kieran Hebden, Jeffrey Makinson, Hinako Omori, Dan Snaith, and the Los Angeles Studio Orchestra conducted by Miguel Atwood-Ferguson at the Hollywood Bowl—a spiritual gathering unlike anything I’ve experienced before. True to the album, but somehow a touch above. Those tears I felt in March 2021 in Amsterdam found me at The Hollywood Bowl yesterday.

And it was only right that it came together like this. Pharaoh's reissue culminates a longstanding “Harvest Time Project” that dove deep into Pharoah’s career and life, ending here in Los Angeles in 2021 at age 82. His stand-in, or maybe instead, his ostensible vessel, was Shabaka Hutchings, who himself is on a spiritual journey, saying farewell to his instrument after this year. Hutchings channeled just enough of Sanders in his playing to not make it a mimicry while sprinkling his own here and there. If Sanders was in conversation with us as listeners on Promises, Hutchings was chiming in with Sanders in the most intimate, respectful way.

A lot has happened between that morning in 2021 and now. There are literally and figuratively almost 9000 kilometers between there and here. I spent the last weekend before my move to Los Angeles in Antwerp, probably as emotional as that run. Luaka Bop’s reissue brings me back to that weekend, with the announcer using his typical Dutch pronunciation to introduce Sanders’ band at Middelheim Jazz 1977 on the live version of Harvest Time. It reminded me of home.

I listened to it on the way to the concert yesterday. Guided by Harvest Time Live - Version 1 in the safe bubble of my earphones and a parade of hipster music nerds, I walked to the Bowl. After seeing the Sun Ra Arkestra perform in their typical space suits, with chaos and acrobatics, the arena turned briefly dark and silent. I heard birds tweeting. crickets chirping. The harpsichord played its first of many repetitions. And I knew I was home again.